Sample Questions Reflecting the Common Core State Standards for Reading

Why I Support the Common Core Reading Standards

This English professor thinks the program's arroyo to reading could ready the problems she sees among her college students.

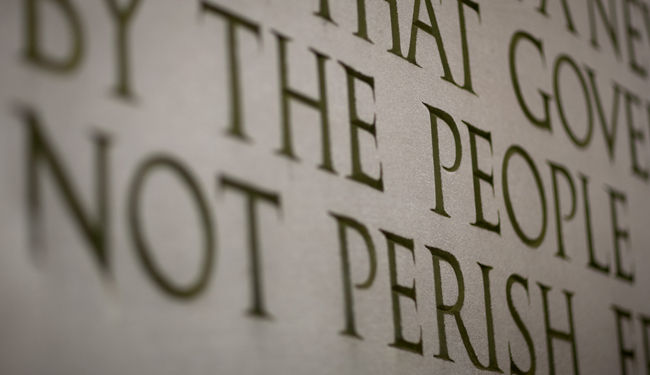

The text of the Gettysburg Address on the wall of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. The Mutual Core proposes having students report the structure and content of such texts in detail, reading for comprehension before emotional connectedness. (Reuters)

"I take reading comprehension." She whispered it, as though it were a communicable disease. The young adult female and I were chatting exterior the meeting room at a prestigious academy where an education symposium was taking identify. She was a higher sophomore, bright, talented, and confident. With a scrap of pressing, I verified that what she meant was that she had poor reading comprehension skills and had struggled with reading throughout all of her school years. Having learned that I was an English language professor, she wanted me to suggest books for her to read; she wanted to bask reading more than. I readily provided, along with some slight condolement.

"Many of my college students have trouble reading," I told her. "And information technology's not your fault or theirs. Students simply aren't being taught how to read anymore."

She nodded emphatically. "I don't feel similar I've ever been taught how to read well," she said.

She is far from alone.

When I was invited recently to attend a two-twenty-four hours conference with David Coleman, president of the College Lath and the main architect of the Mutual Core Land Standards, I was skeptical. With seven years of feel in secondary education and over twenty years in higher education, I've seen a lot of so-called reform. The purpose of my meeting with Coleman, who'd assembled a small-scale grouping of scholars, writers, and, educators, was to explore the land of reading today and the opportunities offered by the Common Core literacy standards for improving reading skills. After 2 days of word with stakeholders united past a love of language and a desire to increase the level of reading comprehension at all learning levels, I was convinced. The Common Cadre'due south "deep reading" approach to literacy and language arts is desperately needed, and volition requite students like the one I talked to at the symposium the tools to be prepared for college, career, and life--tools they currently lack. I know because I see these unprepared students in my college classroom.

Almost ten years agone, I started requiring the students in my general education English classes at the university where I teach (primarily freshmen and sophomores not majoring in English) to sign a "contract" during the start week of the course. They must concord, among other things, to obtain the required textbook and bring it to each class. It might seem odd that in a college class I would have to make such expectations so explicit. Simply in the past decade or and then, I have found that students are seldom if ever held accountable for or even actually expected to read the assigned texts. Years of their so-chosen "reading" is spent "making connections" between themselves and text or the globe and the text, just the foundational step of actually reading the words on the page is neglected oft to the point that really reading the assignment isn't necessary: Students go skilled at responding to leading questions that solicit merely their opinions or experiences. And they apparently become decent, or even excellent, grades for doing so.

Getting my college students to ain and use a literary text hasn't been the only challenge. I have found that, increasingly, I take to teach students to read, actually read, the words on the folio in gild to be able to answer unproblematic questions about the text. I have to train them to expect down at the words rather than looking at me or upward at the ceiling or into their hearts in society to comprehend the meaning of the language. I take to remind them to cite passages as prove when they respond questions, something more and more of them are unaccustomed to doing. I have to exhort them to use dictionaries to look up words they don't know because the arroyo to "reading" they are so familiar with does not depend on knowing the meanings of words. Instead, they have been expected merely to offering "reader-response" answers to questions that prompt readers to react superficially to the text rather than to encompass it. This subjective approach emphasizes loose, personal reactions to texts and interpretations that can not ever exist supported the text itself. So, for example, when I teach William Blake's verse form, "The Tyger," many of my students are erroneously convinced, based on reader-response mode impressions, that the tiger in the poem is a "symbol of evil" when nothing in the text offers such evidence. A colleague of mine recently had a form of students insist with no textual support that Samuel Becket'southward 1953 existential drama, Waiting for Godot, is nearly gay wedlock. Even English majors, I'm finding, rely more and more on Spark Notes summaries because years of lively classroom debates about vague literary themes accept overtaken attention to how authors create worlds through language.

It's not as though the students at my institution are an bibelot: My university enrolls loftier- and low-achieving students and plenty in between, resulting in a student body that closely reflects national averages. Plenty of figures ostend the validity of my own anecdotal show most reading. According to a written report by Deed in 2008, only x percent of 8th graders are on runway for college readiness by the time they complete high school. The National Assessment of Educational Progress indicates that only 38% of 12th graders performed at or above the Practiced level in reading in 2009 (the latest year available for this measure). A 2011 report past Harvard'due south Program on Education, finds the overall rate of proficiency in reading for U. S. students to be 31%. This places the U. Due south. 17th amidst the nations, far from earth leader status. (American higher educational activity, on the other manus, continues to set the global standard.) K -12 teachers, meanwhile, vastly overestimate their students' learning and preparedness for higher. As reported this week in the Chronicle of College Didactics,

while eighty-ix pct of high-school instructors in a simply-released Human action survey described the students who had completed their courses equally "well" or "very well" prepared for first-yr, college-level work in their discipline, only virtually one-quarter of college faculty members said the same thing about their incoming students.

This is why equally someone whose life centers on reading and who is witnessing firsthand the effects of unacceptably low reading proficiency rates, I applaud the reading standards adopted past the Mutual Core.

The language arts and literacy standards of the Common Cadre emphasize careful reading--the close reading of texts to ensure comprehension. These are exactly the skills about of my students lack upon inbound college. This means that rather than teaching literature from the diluted reader-response approach and then pervasive today, the emphasis will be first and foremost on understanding what the text actually says.

Reading comprehension skills are not dissimilar physical muscles: Exercise increases strength. Hence the Common Cadre reading standards also emphasize the quality and complexity of texts that students read. Instead of a steady nutrition of watery kiddie lit, the Common Core requires students to grapple with a broad variety of content-rich, loftier quality texts from across a variety of cultures, eras, and genres. Such texts model for students higher, withal reasonably attainable, models of thinking and writing, better preparing them for career and college. A student volition develop more reading comprehension skills during one 50-minute period spent examining one paragraph from the Declaration of Independence than a week of classroom time spent discussing rad themes in the latest immature-adult novel.

Many teachers themselves have not been taught to teach this manner; indeed many of them accept non been taught to read this way themselves. (I know this considering these teachers take been in my classroom.) But the Common Core Standards for reading include sample questions especially to address this gap: The questions are designed for the teachers to use to cultivate the students' deep-reading skills.

Not surprisingly, some teachers are resistant. They themselves were taught using the quondam practices--the practices that have dominated the academy for the by few decades, and that accept sacrificed reading comprehension to the politicized responses to literature. One instructor recently complained in a post on The Washington Post's website that the CCSS exemplar "narrowed whatsoever discussion to obvious facts and ideas" contained in the Gettysburg Address. Merely it is misguided to call up that much in such a rich and complex a text would be "obvious" to a high school student; this view may perhaps stem from the instructor'southward own superficial reading. Paying attention to a rich text, no matter how elementary the questions seem, e'er opens up insight. Even examining how the significant of the word "dedicate" unfolds in the Address ( expect again: do you observe he uses information technology six times?) gives students access to the movement of Lincoln's thought. The Common Cadre might seem tough-minded and heavy-handed to some, simply when the freight train is dangling precariously off the cliff, it takes ingenuity and muscle to begin to set it aright.

The frustration teachers feel at the constantly changing standards is understandable, as is the sentiment of 1 instructor that his profession " no longer exists": when restrictions pile on tiptop of one another, it seems that at that place is fiddling freedom for the teacher to practise his or her own judgment and expertise. Yet, the fact is that the freedom to teach literary texts was appropriated long ago by politicized special involvement groups who would rather translate Shakespeare, Milton, and Twain using the agenda du jour rather than actually read and sympathise first what Shakespeare, Milton, and Twain are saying. Invisible ideological tails have been wagging the dog of daily classroom instruction for and so long that we don't fifty-fifty know what the freedom to read looks like.

The Common Core standards in reading restore freedom, the freedom of students to be able to read and comprehend a text on their own upon leaving the classroom because they have gained the skills to do and then without the mediation of a instructor-facilitator. The Common Cadre standards in reading are designed empower students to read, and to read well, the very foundation of success for college, career, and life.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/04/why-i-support-the-common-core-reading-standards/275265/

0 Response to "Sample Questions Reflecting the Common Core State Standards for Reading"

Enregistrer un commentaire